HTML Layout is Pain

I’m the first to admit to my being an HTML-dunce. Over time, there’s been the odd need to get my hands dirty with HTML and/or CSS, but it was generally always fairly short-lived and things have progressed so unbelievably far since the late 90’s that it’s fair to say that the territory is now completely different. After all, CSS was only introduced for any practical purposes around the turn of the millennium (yes, my HTML teeth were cut pre y2k; ancient, I know).

As much as putting together an HTML page is largely a case of organising two-dimensional boxes (and their content)—to me, at least, HTML layout has always remained a bit of a black art. When there’s talk about using negative margins as a technique for layout, I start to hear the proverbial scratching of nails on a blackboard. When it’s suggested that such techniques are an improvement on the use of tables for layout, I feel the proverbial tickling of the arches of my shackled feet.

Thank goodness for modern additions to CSS, such as flexbox; they’ve whisked us out of the dark ages of HTML/CSS torture.

The Spec

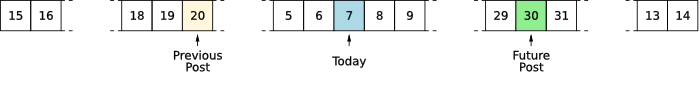

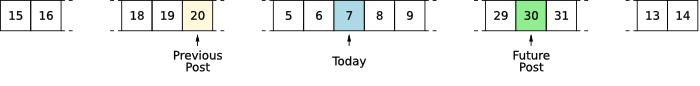

In any case, I have a need—I’d like to render a “bar” of month days, approximately 30 days long, with "today" being in the centre. This I would like to place at the top of my blog, on the home page. Days for-which articles were published will be styled differently from other days, and I may choose to make them clickable to link through to the corresponding article(s). Obviously the latter will be to the left of “today”. To the right of "today" (that is, future days), I would like to style some days differently—these are days for-which I plan to publish articles.

Using my new-found favourite drawing language, namely dpic, let’s draw this out:

The Rabbit hole

This post is going to be somewhat meta, that is, I will be spending most of the post talking about how the picture describing the specification was constructed (as opposed to actually implementing the solution). The former may present some clues as to how to go about the latter—I think that’s a reasonable expectation.

1 .PS 2 3 # Millimetres 4 # 5 scale = 25.4

All pic format files start with .PS; this is a troff macro indicating the start of a picture; correspondingly, the end of the picture is indicated by a .PE. Also, I prefer to do things in metric (millimetres).

6 # Maximum drawing base_size 7 # 8 maxpswid = 300; maxpsht = 500

maxpswid and maxpsht are maximum page size width and height respectively. I ended up having to set these explicitly to some large value since if the drawing exceeds the defaults, then the drawing is scaled; something I didn’t need.

9 # Base base_size for all elements 10 # 11 base_size = 10

I decided to size everything against some base value so that I could adjust things at a later point.

12 # Boxes are to be square 13 # 14 boxht = base_size; boxwid = base_size

The default box is more like a rectangle; I need squares to represent individual days in my “bar calendar”. The built-in variables boxht and boxwid are the respective default height and width of boxes; every box created without explicit dimensions will take on all four sides of 10mm.

19 # Macro: draw a series of boxes, left-to-right 20 # 21 # $1: Starting box label (left-most) 22 # $2: Number of boxes to draw 23 # $3: (Optional) box number to shade 24 # $4: (Optional) Shade colour for chosen box 25 # 26 define boxes { 27 right 28 for i = $1 to $1+$2-1 do { 29 if "$3" == sprintf("%g", i) then { 30 box sprintf("%g", i) shaded $4 31 } else { 32 box sprintf("%g", i) 33 } 34 } 35 }

gpic and dpic both support macros, that is, “macro” as in the C preprocessor or the m4 macro language. The boxes macro draws a series of boxes from right to left, numbering each one incrementally and starting at a given value. Optional additional parameters indicate which box in the series is to be shaded, and the corresponding shade colour.

On line 29, there’s a reference to $3 —this is the third parameter to the macro, and is expanded in-place, as per normal for macros. If a macro parameter isn’t passed through, it expands to the empty string (which is expected), but there’s a need to test for this in order to apply shading to the box. Since macro parameters truly are “verbatim replacement strings”, we need to enclose the parameter in quotes to cater for the possibility that it might be empty. This means that in order to do a comparison, we must also convert the RHS to string form. In dpic we do this by means of the built-in sprintf function.

The dpic reference manual suggests testing for macro availability by enclosing the macro in quotes and comparing it to the empty string:

To check whether an argument is null, put it in a string; for example:

if "$3" == "" then { . . . }

Line 29 originally read:

if "$3" != "" && "$3" == sprintf("%g", i) then { ...

... however, I realised that the first comparison is, of course, redundant, since the second comparison would need to happen anyway.

37 # Macro: Draw dashed lines indicating more boxes to the left/right 38 # 39 # $1: Direction; 1 = right-to-left 40 # -1 = left-to-right 41 # 42 define fadeoff { 43 left 44 line_length = $1*base_size*0.5 45 line line_length dashed; move -1*line_length 46 down; move base_size; left 47 line line_length dashed; move -1*line_length 48 }

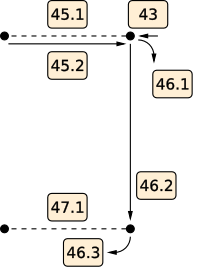

Another macro which allows us to repeat the drawing of dashed lines indicating longer sections of the calendar which aren’t drawn. Depicting the instructions from lines 43 to 47, with intermediate statements indicated by .1, .2 and .3 respectively (in this case, we’re assuming that $1 has the value 1):

No prizes for guessing what I used to draw the diagram above—I had to apply great restraint in not recursing into a meta-rabbit-hole.

50 # Macro: Draw an arrow pointing up to a box 51 # 52 # $1: The 'th box the arrow will point to 53 # 54 define arrowtobox { 55 move to {$1}th box .s; down 56 move 1.75*base_size; up; move 0.25*base_size 57 box $2 invis; 58 arrow to 8/10 of the way between Here and {$1}th box .s 59 }

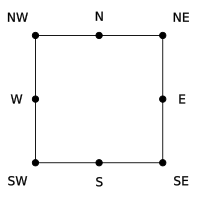

g/dpic come into their own when referring to already-drawn objects; looking at line 55:

move to {$1}th box .s; down

The first macro parameter is used to refer to a previously drawn box in order to designate a start position, more specifically, the "South" point (.s) of the same. Intuitive compass points make it straightforward to refer to points of significance on a primitive:

Done with all this preamble, it’s now possible to draw everything. I’ve included a progress depiction of the script so as to make this seem less like a code-dump:

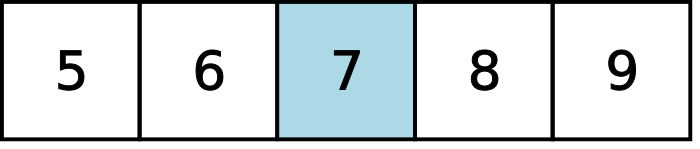

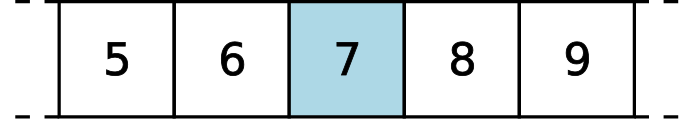

61 boxes(5, 5, 7, "lightblue")

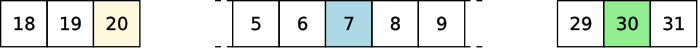

63 move to 1st box .nw 64 fadeoff(1) 65 move to 5th box .ne 66 fadeoff(-1)

68 move to 1st box .w; left; move base_size*5 69 boxes(18, 3, 20, "cornsilk") 70 71 move to 5th box .e; right; move base_size*2 72 boxes(29, 3, 30, "lightgreen")

74 move to 6th box .nw 75 fadeoff(1) 76 move to 8th box .ne 77 fadeoff(-1) 78 move to 9th box .nw 79 fadeoff(1) 80 move to 11th box .ne 81 fadeoff(-1)

83 move to 6th box .w; left; move base_size*4 84 boxes(15, 2) 85 move to 13th box .ne 86 fadeoff(-1) 87 88 move to 11th box .e; right; move base_size*2 89 boxes(13, 2) 90 move to 14th box .nw 91 fadeoff(1)

93 arrowtobox(3, "Today") 94 arrowtobox(8,"Previous" "Post") 95 arrowtobox(10,"Future" "Post") 96 97 .PE

In the next episode of “Boxes and Lines” hopefully I’ll get to talk about what the topic is really about; that is, adding a custom contextual calendar bar to the top of my blog.

Comments !